Somewhere, out there in Winter Park, Florida, a lechon is about to hit the grill. From Cleveland, a planeload of Buckeye boricuas will fly to New York, where Mayor Mike Bloomberg has already begun showing off his emerging Spanish skills. It’s time for the National Puerto Rican Day parade which, much like Cinco de Mayo, is another annual American assessment of all things Latino.

In case you’re lost by now, a lechon is a slab of suckling pig and boricua is slang for Puerto Rican. I knew nothing about this stuff when I was introduced to the Puerto Rican parade 25 years ago after arriving in New York for college. My parents are Peruvian immigrants.

I was fascinated by the enormity of Puerto Rican culture and the conundrum Puerto Rico created for the United States: How could a country have such an uneasy relationship with Latino immigration when it had nearly 4 million Spanish-speaking Latinos born into U.S. citizenship?

The flag of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico looks a bit like an American flag knock-off with one distinct difference: The red and white stripes are joined by a big white star inside a dark blue triangle, a star too big to fit comfortably inside the American red, white and blue.

PUERTO RICAN RELATIONS

That says all you need to know about the U.S.-Puerto Rico relationship.

The Puerto Rican Day parade, held every June in New York City, is an in-your-face explosion of Puerto Rican pride with enormous, colorful floats and blaring salsa music. Pretty girls wave banners for everything from Goya beans to AIDS education. The crowds reach nearly 2 million, building over the preceding week with festivals, concerts and backyard barbecues in all the towns where the diaspora had planted a flag Orlando, Chicago, Boston and the Bronx.

Read Related: The Story Behind Cinco de Mayo

Blacks, whites and Latinos join together in the streets to hear salsa music and express camaraderie. And a long line of cars also heads for the hills.

Back when I went to my first parade, being Latino in the Northeast invariably meant Puerto Rican, which wasn’t a good thing to some folks. People would ask me where in El Barrio, a term for East Harlem, where a majority of Puerto Ricans reside, I grew up, and whether I had papers—meaning immigration papers—even though Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens.

Mostly, people talked about rice and beans for some reason. Did I make them? Did I know where to get some?

Being Puerto Rican wasn’t pretty; it was ghetto, it was barrio, it meant poor.

Even other Latinos would often say that, so I wrote a magazine piece in college saying the rest of Latinos had to drop their own racism and close the wagons around the Puerto Ricans.

In any case, I wore my identity as a mistaken Puerto Rican with some pride. Puerto Rico seemed like Fantasy Island to me, with its bowing palm trees and brilliant sunshine.

Plus, I admired their guts. The island had been a proving ground for colonialism, pharmaceutical companies, economic development schemes and assimilation programs.

ONE STEP FORWARD, TWO STEPS BACK

But the people clung to both their island pride and U.S. citizenship with equal enthusiasm. They even enlisted in the military, although they can’t vote in most national elections.

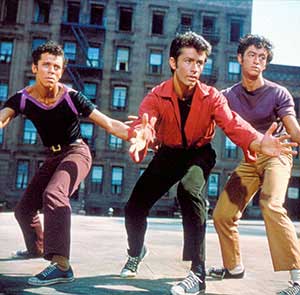

The community had exploded onto the larger public consciousness with West Side Story in 1957, a musical that bestowed stardom on Puerto Rican actress Rita Moreno, who ultimately went on to win an Oscar, Emmy, Grammy and Tony.

The community had exploded onto the larger public consciousness with West Side Story in 1957, a musical that bestowed stardom on Puerto Rican actress Rita Moreno, who ultimately went on to win an Oscar, Emmy, Grammy and Tony.

Yet even this mega-musical had its issues, like the song: America. When the character Rosalia sang, “I’ll drive a Buick through San Juan,” Rita retorted, “If there’s a road you can drive on. But with the Puerto Ricans its always un pasito palante, un pasito patraz (one step forward, one step back).

In the years that followed West Side Story, tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans took a few pasitos northward and migrated to New York, Orlando, Boston and even Cleveland, slowly forming new communities and gathering political power in American cities. They fought to desegregate schools, stormed Congress over Puerto Rican independence and fought AIDS.

The parade was their call to arms, but it had its detractors.

The community struggled with an event that had grown large and unwieldy. Some objected to the half-naked girls, commercial floats, excessive alcohol and mafia-like sponsorship structure. A few bad spectators soiled the image further when several years of parades ended with mass arrests for gang activity and assaults on women.That was exactly what the Puerto Ricans didn’t need when there was so much derision floating around on the mainland.

In 1979, Coach Bob Knight, a darling of college basketball, punched a police officer on the island during the Pan American Games, and told Sports Illustrated the only thing Puerto Ricans know how to do is grow bananas. Cosmo Kramer, a character on the wildly popular sitcom Seinfeld, accidentally stomped and burned a Puerto Rican flag in one of the highest-rated episodes. A Puerto Rican named Mark Lyttle was mistakenly deported to Mexico because he couldn’t produce his birth certificate for U.S. immigration agents.

PUERTO RICANS CAN DO ATTITUDE

But Puerto Ricans are like the Little Engine That Could. By the late 1990s they had their own Barbie doll, even if she was light-skinned and wore colonial attire. They also had their own legal defense fund and elected people to Congress. State Farm caught hell when it tried to use Knight for an ad. So did Coors when it marketed beer during the parade with the slogan Emborícuate, or “Become Puerto Rican” in Spanish, which sounded too much like emborachate, or get drunk. By the time the film version of West Side Story was released, Rita was singing life was all right in America. And Rosalia would shoot back, If you’re all white in America. Indeed.

The last time I went to the parade, I had just finished producing a documentary called Latino in America with CNN anchor Soledad OBrien. We wanted to publicize it to Latinos.

I was struck by how broadly the parade had been embraced.

This daughter of Peruvian immigrants hopped on the El Diario La Prenza float alongside a half-Cuban, half-Australian news anchor and took both our kids for a ride up Fifth Avenue through screaming crowds. There were Venezuelans, Panamanians and white couples from the Upper East Side. We hoisted her twin boys on our shoulders and dipped into the crowd to hand out CNN pins. My daughter, whose father is Puerto Rican, passed out tiny flags. It was really exhilarating to be in one of those truly American moments, when our differences become cause for celebration.

So are we finally all Puerto Ricans for even that one Sunday in June?

The New York Daily News ran a full-page ad saying it was sponsoring a float with New York Giants wide receiver Victor Cruz, who is known for his salsa dancing. The newspaper had just laid off the staff of its Latino edition, so that didn’t sit well with some Latinos looking closely at the huge flag unfurling at the top of the ad. It has blue and white stripes with a white star inside a red triangle—Cuba’s flag.

Guess the Puerto Rican one didn’t quite fit.

A contributor to Mamiverse, Rose Arce is a senior producer at CNNs New York Bureau. She was a senior producer of Latino in America 2, which re-airs July 22 on CNN. For the full version of this article, click here.