Karina Quezada knows what can happen when a parent places too much trust in their child’s teacher. In her native Mexico, a teacher berated Quezada’s eldest son for writing with his left hand. Later, in Houston, another teacher used her son as the translator for his entire second-grade class.

In both instances, Quezada only learned about the incidents after her son came to her upset and crying.

Now, Quezada is determined to be an active advocate for her three children. She volunteers at their charter school, nurtures a close relationship with their teachers, and even works occasionally as a receptionist in the Houston school.

“It’s very important to know the person who is teaching your children,” said Quezada. “In Mexico, the teachers have all the power because parents give them the power. Here, it is different.”

Countless studies have shown that parental involvement is often the key between student failure and student achievement.

Knowing that a parent is staying on top of grades, keeping an eye on their child’s attitude and behavior in class, and aware of assignments and coursework often increases student motivation. It also alerts parents to any problems that might pop up with their child’s teacher, ranging from personality conflicts to classroom abuses.

Read Related: Imagine the Life of a Teacher

A 2007 study by the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute noted: “Teachers, counselors, and principals did not hesitate to attribute high academic achievement to greater parental involvement. As one counselor reported, ‘The [academic] level of the student is indicative of the level of parental involvement.’ ”

However, many Latino parents, raised with the belief that teachers should not be questioned or challenged, are reluctant to contact teachers or get involved in school matters.

In addition, immigrant parents may feel shut out of the school environment by language barriers or feel ill-equipped to help children with homework or school assignments, the 2007 Tomas Rivera study found.

“The parent is obligated to check if the homework was done completely; the teacher is obligated to correct the homework,” one respondent told the researchers.

Several of the parents interviewed believed that they only needed to contact teachers if there was a problem in school.

However, by placing too much trust in teachers, Latino parents may be inadvertently limiting their child’s achievement in school.

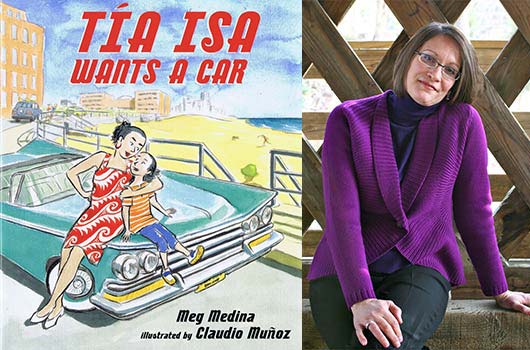

In her recently released book, Hispanic Parental Involvement: Ten Competencies Schools Need to Teach Hispanic Parents, Dr. Lourdes Ferrer says that parents should think of themselves as part of an educational tricycle, in which the student is the front wheel and the teacher and the parents are the rear wheels.

Ferrer, an educational consultant who specializes in minority student issues and parental involvement, says Latino parents must master 10 competencies to help their children do well in school:

- Value their child’s education

- Meet their child’s basic needs

- Overcome immigrant challenges

- Maintain family unity

- Understand their own role

- Believe in their child

- Connect with the teacher

- Make reading a lifestyle

- Make homework a routine

- Build character

“Because the view of family is such a significant factor in the Hispanic culture, any interventions to improve the academic achievement of Hispanic students must include partnerships with the parents,” Ferrer concluded in a 2007 report examining the reasons behind low achievement by Latinos students.

“The parental issues that the students mentioned do not have easy solutions. I know that we cannot resolve them all at a school level; however, unless we find a way to engage parents in partnerships, none of them will be resolved.”

For Karina Quezada, becoming a more active participant in her children’s education has already proven beneficial.

Her oldest son graduated this year and is headed to Texas State University in the fall, and her other two children are thriving in KIPP Academy charter schools.

“The teachers all know me. If there’s a problem, they let me know right away,” said Quezada. “And I know them well enough to trust them.”