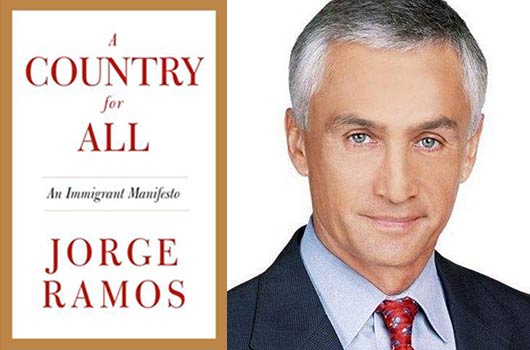

Editor’s note: This post is part of a series on immigration leading up to our Twitter Talk on February 13 at 9pm EST with Emmy-winning journalist Jorge Ramos. To take part in the conversation, follow #CountryForAll on Twitter.

As a much-awaited immigration reform proposal finally emerges in the United States, my heart sinks when I read the news about Spaniards immigrating to Latin America and being rebuffed there. It makes me remember when I lived in Spain (I am half Spanish) and I was witness to discrimination against Latin American immigrants.

It struck me as ironic then and it still does now, since so many Spaniards had to emigrate to Germany, South America and the United States after the Spanish Civil War. My own great uncles migrated to Venezuela and then to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. And my father followed at 16 years old as, in post-WWII Spain, food was scarce and the opportunity for getting an education slim. He put himself through college here, and became a university professor at a very young age. He met my American mother, and the rest is history. That is how I enjoy being bilingual, bicultural and—best of all—a dual national.

Now Spaniards are fleeing Spain again because the country is in dire straits. And they are seeking refuge in the very countries whose citizens were once unwelcomed in Spain…the tables turn again.

Join the Conversation: Mamiverse Twitter-Talk with Award-Winning Journalist Jorge Ramos

It is unlikely that people decide to pick up and move to a different country—where they may not even speak the same language—to freeload and try to get by without working. The majority of people immigrate because they are oppressed in their homeland or they seek better economic, employment or education opportunities. For many, their migration starts out as a temporary situation that becomes long-term or permanent; most would like to return to their home countries, but cannot for a variety of reasons: cultural, financial or personal. And while they strive to maintain ties to their culture of origin, most do try to adapt to the country to which they’ve moved, even in the face of bigotry, obstacles and isolation.

I’ve never had to fear being deported. But I have friends and even family who have been in that situation—and these are hard-working honest individuals. With few exceptions, immigrants are feared, loathed or both. At best, they’re viewed as “the other”—apart from the society in which they’re trying to assimilate. In Spain, Cubans, Mexicans, Venezuelans, Peruvians…are not welcomed by society at large. As a result, those who immigrated to Spain out of need create their own ghettos and live in poor conditions, even sharing a bed with a stranger (cama caliente: where one of the tenants sleeps in it at night, the other during the day).

And now, Spaniards find themselves as the huddled masses of Latin America, unwanted, and in the same conditions as those they were unwilling to help in their own land. Is this righteous comeuppance, or is it another sad commentary on the human condition—are we just xenophobic by nature? With financial globalization, overpopulation, and the looming threat of food and water shortages as a result of climate change, the entire world’s willingness to open its borders to strangers in need may well be tested, and in our lifetime.

The United States is still the Promised Land for so many of the world’s impoverished immigrants, but can we imagine a scenario where residents of the U.S. are driven to emigrate, in search of jobs and opportunity, or even—as in my forbearers’ case—for food? The nations of the world tend to welcome American immigrants now—they even have an elitist name, expatriates—but that’s because it’s mostly wealthy intellectuals, doctors, and artists who seek to live and work abroad. If Americans arrived in droves on foreign soil, in search of jobs in factories, fields and service industries, would they be so welcomed?

Join the Conversation: Mamiverse Twitter-Talk with Award-Winning Journalist Jorge Ramos