When American journalist Pamela Druckerman moved to Paris with her husband and had a baby, she began to realize that French children were very different from American children. They behaved politely in restaurants, ate anything their parents put in front of them, slept through the night, didn’t scream, and played alone nicely while their parents chatted with friends. What’s more, she observed French mothers recovered their figures within three months of giving birth and wore fabulous heels at the park for playdates! How was it possible?

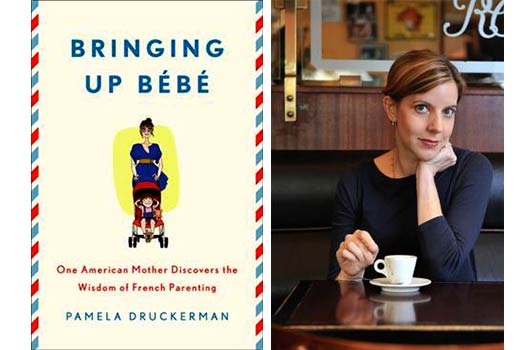

Druckerman began to investigate, inquire and compare cultural differences specific to having and raising babies. The result is a delightful book entitled Bringing Up Bébé, in which the author compares French and American parenting styles and tries to find a happy medium. I recently had the opportunity to ask Druckerman a few questions about the book and what she found through her research and her own experience as a parent.

Mamiverse: How would you describe your ideal parenting style?

Druckerman: I think it’s very important how the French listen to kids, and understand their perspective. But they think that just because you listen to a child, you don’t have to do everything he says. In America, there’s a spirit of optimism and risk-taking that I really admire too. It’s nice that when we’re back home in the U.S., my kids are the focus at family gatherings and dinners. I hope they’re getting a good balance between the two cultures.

Mamiverse: If you had another child, which key aspects of each system would you apply?

Druckerman: One example of the French applying simple principles that really do work is with food. They tell children, ‘You don’t have to eat it all, but you do have to taste it.’ They keep re-proposing the same food dozens of times, prepared many different ways. All this tasting helps to turn many French kids into little gourmets. The lunch menu at my daughter’s day care looked like the menus at a French brasserie—four courses, including a different cheese every day. Plus, in France there’s typically no snacking between meals (only one ‘official’ snack time in the afternoon), so kids come to the table hungry. Then parents serve vegetables first. The extreme pickiness about food that’s come to seem normal in America looks, to French parents, like a dangerous eating disorder, or at best, a wildly bad habit.

Mamiverse: What do you think is the greatest and most urgent problem to solve in the education of American children?

Druckerman: The French think that kids need to learn to cope with a bit of boredom and frustration. They consider this a crucial life skill, and something their kids can’t be happy without. They think kids need activities, but they also need lots of free time just to play. A recent round-up of neuroscience research says that exploratory play teaches children persistence and improves their attention spans, confidence, and creative problem solving skills. It’s also fun.

Mamiverse: You are very critical of the American tendency to speed through stages of development, as it encourages competitiveness. Do you prefer the French concept of inviting children to “wake up” to experiences and enjoy them?

Druckerman: American parents often want their kids to learn how to read as early as possible. French parents tend to focus on teaching little kids ‘soft’ skills like how to socialize, and be empathetic. One simple, daily way they do this is just by insisting that even little kids say hello and goodbye to adults (not just please and thank-you). They believe that the simple act of greeting people helps kids realize that other people have needs and feelings too.

Read Related: The Benefits of Non-Attachment Parenting

Mamiverse: French Mothers typically recover their figures in three months, do not lose sex appeal or seem to lose themselves to breastfeeding. What do you think of this model?

Druckerman: The French ideal for mothers is to have a balance. No one part of life is supposed to overwhelm the other parts. They believe that for the baby’s first few months a woman should devote herself entirely to the child, but that after that the baby can gradually start fitting into the rest of the family’s rhythm a bit too.

Mamiverse: You also say that French mothers are better at managing their guilt. How can the Americans learn from that?

Druckerman: Guilt, like anxiety, is valued in America. It’s viewed as a sign that you really care about your kids, and a check on becoming too selfish. French moms do battle with guilt too. But they don’t value guilt; they think it’s unhealthy and unpleasant. And while they think it’s crucial to be in close communication with your kids and to spend time with them, they think it’s unhealthy for kids and their moms to be together constantly. As an American mom, I’ve sometimes benefited from hearing the French mantra: The perfect mother doesn’t exist.

Mamiverse: In France, parenting websites advocate for children not to invade the entire universe of the parents. Is this the most difficult thing to conquer for American parents?

Druckerman: A household that’s centered entirely on the children is no fun for parents, but it’s probably not even good for the kids! When a child interrupts in France, his parents aim to politely say to him, ‘I’m in the middle of speaking to someone, I’ll be with you in a minute.’ This respect is supposed to be mutual. When a child is happily playing, his parents try not to interrupt him either. This takes practice, on both sides. But eventually, it can reign in the chaos of family life a little bit, and makes being together more pleasant.

As “intensive parenting” has become the middle-class norm in America in the last 20 years, marital satisfaction has declined and divorce rates have risen. Reports suggest that parents are less happy than non-parents, and they become even more unhappy with the arrival of each additional child. French parents are far from perfect, of course. But they’re a kind of counterpoint to what’s happening in the U.S. and perhaps we can learn a thing or two from observing parenting styles in various cultures around the world.