Recently on NBC’s Rock Center with Brian Williams, Chelsea Clinton gave a news report on the collaboration between a charter school in Rhode Island and the surrounding public schools. The goal of this venture is to help the public school children in kindergarten through 2nd grade improve their reading skills… and it is working. When this collaboration began three years ago, only 37% of K-2nd graders were reading at or above grade level. Within eight months, that number was up to 66%.

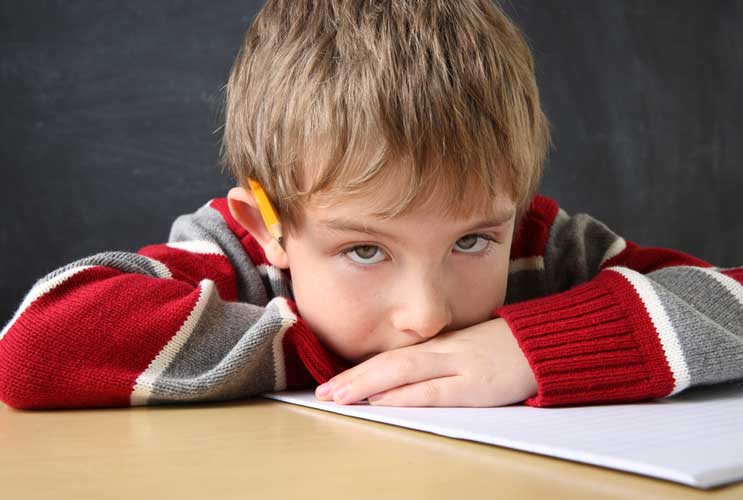

This particular Rhode Island school district is the poorest in the state, and many of the students are Latino children. Their situation, though, is reflected across the country. According to the School Library Journal, our country’s graduating high school seniors in 2011 only had a 31% proficiency rate in reading. Harvard’s Program on Education Policy and Governance has released a study “Globally Challenged: Are U.S. Students Ready to Compete?” that reveals that this proficiency rate really varies depending on the ethnic and racial background of the student. The numbers are even lower for Latinos. Barely 5% of Hispanic students ranked proficient in reading, according to the study.

Literacy is one of the top skills necessary for a student to succeed academically. If you can’t read and write, or understand what you are reading, it affects virtually every subject across the board. Almost every class requires reading. Even in math, you have to be able to read word problems, or at least the directions.

Read Related: International Latino Book Awards Winners

One of the things that struck me the most about Clinton’s report was that the “innovative” strategies the charter school was sharing with the public school teachers were actually not new techniques. I’ve used them with my own children in teaching them to read. I learned about them through the curriculum I use. And, having been in the field of promoting literacy for a few years now, I know that other parents and teachers know about them, too.

So the question is, why aren’t Latino parents helping their children? It certainly isn’t due to a lack of interest; Mamiverse’s own recent study shows that online Latina moms are very much concerned about education and their children’s academic success. (Sixty-one percent of Online Latina moms ranked education as one of the top two issues in the upcoming presidential election, second only to jobs by a statistically insignificant 1 percent.) So it seems that perhaps they just don’t know how to best help their kids learn to read.

I strongly recommend that schools across the country develop bilingual parent guides that describe the different techniques parents can use at home to help develop their children’s literacy skills. Armed with the knowledge of how they can help their children excel in school, Latino parents can—and will—work towards preparing them for academic achievement.

For those of you with young readers, here are some of the strategies the Rhode Island school district is using, as well as others, that promote reading comprehension and a love for reading and writing.

Read, Read, Read

The number one thing you can do to help your child become a great reader is to read to him for 20 minutes a day. Typically a bedtime ritual, there’s no law against reading at any other time! And those 20 minutes don’t have to take place all in one sitting. The goal is to read for a total of 20 minutes a day. This experience helps them to master language development and builds their listening skills. It also increases their attention span and teaches them to focus for long blocks of time.

Talk About the Cover

When you first sit down with a book, look at the cover together and discuss the picture (almost all children’s books have an illustrated cover). Ask your child what she thinks the book is going to be about. Then open it up and read to see if she was right!

Use Your Body

When you read, do it with expression. Use different voices (and even accents!) when you read the words of different characters. Vary your pitch to keep the story engaging. As you read, be sure to point to each word. Your child will soon learn that sentences begin with a capital and are read from left to right. He will even start to recognize frequently used words.

Ask Questions

Take time to pause while you are reading the story to ask your child questions about the story line. Why do you think [the character] did that? What did [the character] mean when he/she said…? What do you think is going to happen next? All of these are good questions that challenge your child to think about the story as a whole and not just the words being read. Also, when you finish the book, ask your child questions about things that happened in the story. Who were the characters in the story? What happened first? Last? Did the character have a problem? How did he/she solve it? Where did the story take place? All of these questions teach your child about the different parts of a story, such as the setting, the characters, the conflict, and the resolution.

“Sketch It”

After you’ve read the story, give your child some paper and crayons/markers and ask her to draw some pictures to go with the story. You can be specific and ask children to draw something in particular, or leave it up to the child to use their imagination. I like a combination of both, sometimes asking my children to draw a certain scene or character from one story, then asking them to create their own “illustration” for the next. Children can draw about something they read in the story, or draw their own version of what happened afterward.

“Connection”

After reading a story, ask your child if they’ve ever experienced a similar situation, met a similar character, etc., in their own lives and encourage them to tell you about it. By relating the story to their own lives, children develop greater interest and are more likely to think about the elements of the tale.

“Retelling” (Also known as “Narration”)

This technique is a favorite among Classical Education instructors. It really develops reading comprehension and simply involves asking the child to tell you the story in their own words after they’ve heard it. You can prompt them with specific questions, if they are unclear. But don’t expect a long, word-for-word description. Keep it short and simple.

Write It Out

For older children, you can ask them to write up a description of the story (in a written version of Narration), or write a continuation of the story in their own words. The goal of this exercise is to get them to enjoy writing, so don’t critique their spelling or grammar. Instead, praise them for their hard work.

By using these techniques with your beginning readers, you can help them grow into confident, skillful ones. As parents, we have the opportunity—and the responsibility—to encourage and develop our children’s literacy skills. Knowing you’ve played a major role in your child’s academic achievement is worth far more than a thousand words.