Murderous mothers, mothers who kill their own children. Impossible?

The unconditionally epic miracles of pregnancy and motherhood are so universally regarded with positivity, warmth, bonding and an unwavering sense of maternal protection—that making sense of a woman who kills her own child indeed seems like the mother of all surreal inconsistencies. But the numbers tell a disturbingly different story.

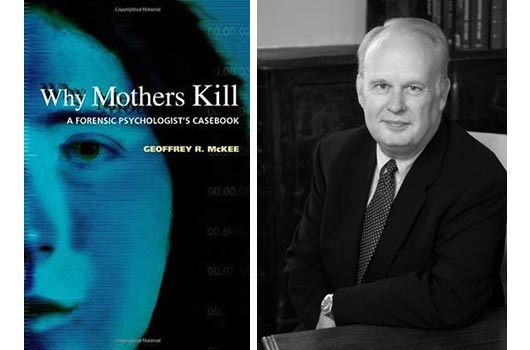

According to the American Anthropological Association, more than 200 women murder their children in the United States each year. However, as headlines might suggest, that number is much higher. In fact, in his book, Why Mothers Kill, Forensic psychologist, Geoffrey R. McKee, cites 2001statistics that showed that 1,300 children died due to abuse or neglect by their parents or caretakers, that 390 children—one child each day—were killed by their mothers. These are the littlest victims, as he cites that 85% of the victims were less than 6-years-old and 41% had not even reached their first birthdays. Most harrowing is the fact that the numbers are likely even higher, given that some murders go undetected, as in cases of young mothers who flush newborns down toilets or leave them to die alone in dumpsters.

The parents of accused murderer Casey Anthony.

It’s safe to say that most people think of the Yates case a perverse fluke of nature. But what most of us don’t realize is that this case “was actually an indicator of a real phenomenon that is more common than any of us can possibly imagine,” according to Michelle Oberman, professor of law at Santa Clara University and co-author of the 2008 book, When Mothers Kill: Interviews From Prison. She adds that “the conditions giving rise to filicide vary across different cultures. For example, in cultures that show strong preferences for male offspring, one tends to see female infanticide. In the U.S., the crime tends to be linked to the mother’s profound social isolation; this stands in contrast to the Latin American cultures that I have studied. It is way more common in the latter to have extended family living in proximity and to be able to call on family for favors. To the modern American, it is oftentimes seen as ‘a drag’ that your mother-in-law lives in your house, as some might be inclined to think that this is ‘old country’ behavior; but I actually think this is a life-saving feature for a new mother—just having that extra set of hands around, and someone who has their eye on you.” Oberman notes that in the case of Andrea Yates—despite her known mental illness—people outside of the nuclear family were not allowed to take care of the Yates children, ranging in age from 6 months to 7 years.

According to Oberman, it is a uniquely modern notion to think that a woman should be able to stay home alone with five children under the age of seven and perfectly handle it without a hitch. “It is the first time in the course of human history and in contemporary U.S. society that we feel that this is a reasonable way to raise children. When you look back into history what you really see is women living in proximity to other women and extended family, so that there was always someone there to take care of the new mother, supporting her in the process of caring for her babies and any other children she might have.”

SOCIAL ISOLATION

Oberman also notes that while it is true that these crimes are all unique in the details that distinguish each of these horrific incidents, when assessed from a distance, there is a very consistent pattern of social and emotional isolation among the girls and mothers who commit this crime. “These women feel a sense of being unable to share their desperation, and in fact, are unseen or invisible. Consider the crime involving a teen-aged girl who commits neonaticide, where she conceals the fact that she’s pregnant and doesn’t tell anybody. This is the girl who delivers her baby unattended, with no neo-natal care, in the bathroom, and maybe thinks that she’s having a bowel movement. Our first instinct is to think that these teenagers are straight-up devils. And yet when you look a little more closely, you find that they are so emotionally isolated, and that there really isn’t a single adult in their lives that they can trust. Nobody notices that they are pregnant—not their mother, not their father, no one—which of course begs the question: How do you not notice that someone is pregnant? The answer is that these are households where people simply aren’t touching; there is no hugging. Lots of times these girls who wear loose clothing, or girls who don’t gain that much weight; some are overweight girls whose pregnancies are camouflaged by their heaviness. The physical part is only one side of it, though. The essence of what’s really going on is that no one talks to these girls; there is nobody with whom the girls feel safe.”

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

As Oberman sees it, “the pattern of social isolation in this country is dominant and terrifying because we are moving into more and more of an atomized society, where we live at a distance from our family members, and often times don’t even know our neighbors well enough to ask for help. We stigmatize mental illness or struggles with motherhood so that real mothers are afraid to say, ‘This is hard, I need help.’ Or, we don’t train medical experts well enough to ask hard questions of new mothers, so that these mothers come in with new babies for pediatric visits and the doctors typically ask, ‘How’s the baby doing?’ But seldom are the mothers’ asked how they are doing. We miss these opportunities, knowing that a lot of mothers struggle in the first few months of adjusting to motherhood.”

Though mental illness is surely one of the reasons that filicide occurs, according to Oberman, the majority of filicidal cases involve neglect. A woman who never noticed that her baby isn’t gaining weight, leaves her baby alone in the bathtub or car because she needs a break or shakes her baby in attempts to quiet it, for example. Those are scenarios that have to do with isolation and poor parenting issues, Oberman says.

PATH TO PREVENTION

By having honest conversations about what’s difficult with pregnant women and new moms, and by anointing ourselves as the extra set of hands for women we know with new babies, we can begin to break the taboo of motherhood and stop pretending like it just comes naturally and is the most instinctive job that women do. Just showing up and saying, ‘can I hold your baby while you take a shower?’ or ‘I’m at the store, do you need anything?’—basically making yourself available to someone who appears to need help. The primary way new moms can be helped is by making it safe for them to talk to about the struggles, as easily as the joys of motherhood, Oberman suggests.

The secondary way we can help is by getting to know the resources of the community and helping women feel that it is okay to drop off your child at a daycare once or twice a week, or every day if you have to, and it doesn’t make you an awful person. The bottom line is that we need to stop condemning mothers who want and need breaks, Oberman says.

According to Professor Lita L. Schwartz, Ph.D., ABPP, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Humanities/Social Sciences at Penn State University and co-author of the book, Endangered Children: Neonaticide, Infanticide, and Filicide, the following are among additional reasons women commit such a seemingly inconceivable act:

- Shame or humiliation: Negative feelings about being pregnant or a mother and unmarried.

- Anger at the father: Perhaps because he does not admit to being the father or does not provide support for the child.

- Mental illness: She perceives the baby as some kind of menace/threat to herself—not as a needy little human being.

- Religious/ethnic views: Over the past few centuries, there have been some perceptions of children somehow being allied with Satan, resulting in the parent feeling justified in committing filicide. While it may seem strange and even bizarre to many of us, in the mind of this parent, filicide is more desirable than an alliance with the devil.

- Ignorance of parenting role: She does not know how to care for a child, and/or perceives the child as a burden to be eliminated.

Oberman agrees. “There is not so much of a distance that separates me from the unthinkable,” says Oberman. “That’s the mistake we make as a culture: assuming that there are two kinds of women—those who would harm their children and those who would never harm their children.” Ultimately, she adds, we need to start viewing “struggles with motherhood” as a wide-ranging spectrum, ranging from being overwhelmed by the challenges of parenting on one end to the horrific act of filicide on the far end.