EDITOR’S NOTE: The Librotraficante Caravan will begin in Houston on March 10th and arrive in Tucson on March 16th. The Arizona city has been the focus of media attention due to a ban on Mexican-American studies by the Tuscon Unified School District. This is the first of many pieces Tony Diaz, a self-made will write on the subject for Mamiverse. Librotraficante means “book trafficker.”

Deciding to make the Librotraficante Caravan a reality was a moment in my life when my love for my sons and my passion for literature fused into one. Bringing banned books into Arizona is, for me, like making sure my own children have the right to see and think; providing them, and all children in Arizona like them, with a chance at better understanding who they are, where they come from, and most importantly, who they’ll be.

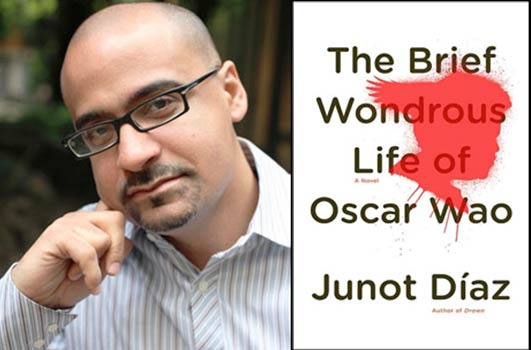

My oldest son, Antonio, is 11. When he was just a baby, he met Pulitzer Prize-winning author Junot Diaz, who said to me: “That kid’s going to Harvard.” Of course, since Stanford has the most extensive collection of Mexican American writings—I’ve pushed for Stanford. Since then, Antonio’s been to several readings by Sandra Cisneros and even has an as-of-yet unreleased poem that she gave to him as a gift.

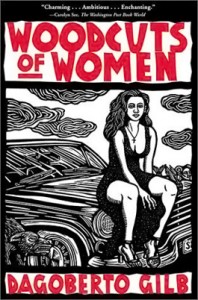

My youngest son Pablo is 7. When Guggenheim-fellow Dagoberto Gilb visited his grammar school, Pablo walked up to him and politely said, “Hello, Dagoberto. It’s nice to see you again.” I think it is the epitome of the American Dream that my sons will some day take this for granted. They will see a fellow Latino and wonder if he or she writes poetry or prose, or wonder if she has a PhD or Master’s Degree.

LATINO LITERATURE FREED MY MIND

My parents were migrant workers. I was the first to go to college, let alone earn a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. The same can be said of each of the amazing authors I just named. If you are the first in your family to earn a college degree, you have made an impact for generations to come. Nothing tells me that more than when my son walks into our house and nonchalantly tells my wife, “Dad brought Dagoberto to my school.”

Read Related: 10 Ways Your Local School Board Impacts Your Life

I think about the luck involved in getting me to this point. I think of the blood, sweat, and tears poured into my education. My mother and father knew that an education would give me the life they never had, would guarantee that I didn’t have to work hard the way they did. On the other hand, as for many of us, my first job as a child was to translate the outside world into Spanish for my parents. Now, my job is to translate my culture for the rest of the world. That is the case for many of us.

But even having said all of this, the first time I read a book written by a Latino writer was when I was a junior in college. I was a junior at De Paul University in Chicago. I was enrolled in a Creative Writing workshop with Professor Ted Anton. After I would turn in the short stories that I wrote for our workshops, he would ask me why I didn’t write about my culture, my background. I forget what I told him, but I do remember thinking, “How? Why? Can I?” One day near the end of the semester, he handed me a novel titled Down These Mean Streets written by Puerto Rican author Piri Thomas.

But even having said all of this, the first time I read a book written by a Latino writer was when I was a junior in college. I was a junior at De Paul University in Chicago. I was enrolled in a Creative Writing workshop with Professor Ted Anton. After I would turn in the short stories that I wrote for our workshops, he would ask me why I didn’t write about my culture, my background. I forget what I told him, but I do remember thinking, “How? Why? Can I?” One day near the end of the semester, he handed me a novel titled Down These Mean Streets written by Puerto Rican author Piri Thomas.

That book changed my life. I had never read an author who code switched from English to Spanish, in one sentence, to Spanglish, like Piri Thomas did. He wrote about his familia. He wrote about being ostracized in New York. He wrote about not just being Latino, but also Black. And it blew my mind. It freed my mind.

BOOKS MUST BE PART OF OUR LATINO LEGACY

I began to understand that I, too, was a part of this legacy of literature that I loved so much. Now, I could walk into a book. Had that never happened, I would not have gone on to earn a Master’s degree, only the third Latino to do so at the University of Houston’s Creative Writing Program. I would not have gone on to win the Nilon Award for Minority Fiction.

I would not have gone on to found Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say, a nonprofit that is now 13 years old, whose mission it is to promote Latino literature and literacy. I would not have had the privilege to work with young, great writers who would go on to become great thinkers, great activists, successful professionals in all fields, who helped me organize the largest book events in Houston, for any demographic. Without a doubt, our words have changed Houston for the better. I tell you all this because this experience, the power unleashed when we are exposed to books that touch our hearts, minds, and souls is in jeopardy.

Right now, it is against the law to walk into a classroom in Tucson, Arizona and teach the wonderful book The House On Mango Street. The fact remains that it is illegal for me to walk into a classroom in Tucson and teach Dagoberto Gilb’s book Woodcuts of Women. The state of Arizona devised a law that set forth certain criteria for determining if a course should be “Prohibited.” And as with Prohibition in the U.S., the law serves to ban something, in this case a course and the books taught in the course, especially if the course or book advocates “the overthrow of the government.” These are exact words in the law.

Right now, it is against the law to walk into a classroom in Tucson, Arizona and teach the wonderful book The House On Mango Street. The fact remains that it is illegal for me to walk into a classroom in Tucson and teach Dagoberto Gilb’s book Woodcuts of Women. The state of Arizona devised a law that set forth certain criteria for determining if a course should be “Prohibited.” And as with Prohibition in the U.S., the law serves to ban something, in this case a course and the books taught in the course, especially if the course or book advocates “the overthrow of the government.” These are exact words in the law.

Woodcuts of Women is a collection of short stories. Nowhere in it is there a mention of overthrowing any government. However, these books can cause some upheaval. By embracing this literature, I was able to go from not knowing my artistic ancestors, to supporting their work, to meeting them, to having them walk into my living room to meet my baby boys. This is how education and literature changes lives. This is what is being denied our young. As the Tucson school district plays with words, they are also playing with lives. However, we have been endowed with the tools to do something about this.

What will you tell your grandchildren when they ask you where you were during the Librotraficante Caravan of 2012? Tell them how you stood up for the students in Tucson, tell them now you defended culture, tell them you defended their right to Freedom of Speech. Tell them you acted to ensure that some day, they had the right to tell their story.

Tony Diaz is the author of The Aztec Love God and holds a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. He is also an entrepreneur, who brings together contemporary Latino arts, culture, and business in ways that have transformed Houston. He is the founder of Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say,which oversees several successful approaches to the Latino experience in the U.S. These range from unique websites, to classic media such as the magazine Aztec Muse and the group’s weekly radio program.