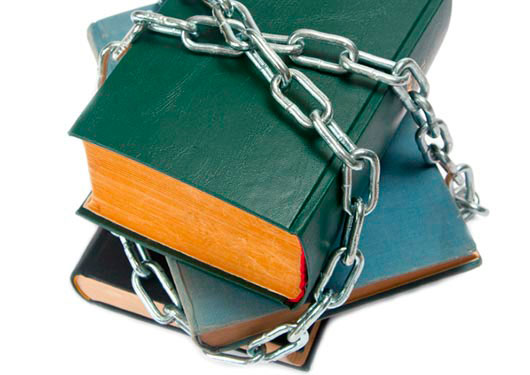

The new Arizona mandate to end the Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican American studies classes this week had school officials boxing and carting out of classrooms books that deal with oppression, race and ethnicity, including those pictured here. School district officials have told news sources the books aren’t banned, just removed from the classroom in order to comply with the law. They say the books will still be available to students through their libraries.

Still, I’m angry. Not because I’ve read all these books (I haven’t, though I’m familiar with some of the writers), but because of what books have meant to me since I learned to sound out the words and turn their pages. I grew up in Las Cruces and El Paso, a kid who today would be considered “disadvantaged” or “at risk.” My geography consisted of a small strip of Texas-Mexico border, a handful of nearby cities, and occasionally, as far south as Delicias and Chihuahua. Because we didn’t take ski trips or European vacations, books constituted a passport to lands, lives and issues otherwise closed to me. Books were my key to the universe. And while my parents had very strict rules by which my brother, sister and I were to abide, books seemed to fall outside the jurisdiction of any of them. Though between them they might have had only an elementary school education, my parents seemed to know there was something inherently important about books—something that scares some Arizona lawmakers, as well as others across the country so much that they feel the need to challenge certain writers and their work. Why else would they have allowed me, a Mexican-American kid, to read anything and everything on which I could get my little hands?

My parents were Mexican immigrants who believed their kids should have an education—the kind you got at home as well as the one offered at school. Therefore, my siblings and I did not talk back to them or to any adult who came into the sphere of our lives. We did not misbehave in public. We were to properly greet anyone who walked through our door. Any infraction of these rules would earn us a good spanking. We had an aunt who lived with us for years and when a boyfriend once came to pick her up for a date, I was in a bad mood. My mother told me to shake his hand, and instead I picked up a saltshaker and threw it at him. I missed, but not by much. He marveled at my aim. My mother, on the other hand, marveled at her daughter’s bad manners and spanked me right there in front of him. My parents’ strictness extended to other areas—no sleepovers at home or at other kids houses for instance, and certainly no dating until they said so.

Read Related: The Making of a Librotraficante: Smuggling Books into Arizona & the American Dream

FREEDOM IN BOOKS

FREEDOM IN BOOKS

Yet when it came to books, my parents gave us an inexplicable, incredible free rein. Perhaps this was due in part to their own poverty growing up; though we’ve not talked about this before, I imagine that in their childhoods there was a dearth of books. So for as long as I can remember, we had library cards and we borrowed books written in both Spanish and English. When we received book order catalogues at school, we were always allowed to buy several. One elementary school teacher, Mrs. Beckett, read chapter books aloud to us. Two that I remember are Wilson Rawls’ Where the Red Fern Grows, and Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. It would be decades before I learned that the latter is among the 100 most banned or challenged books of all time.

When Mrs. Beckett read the Rawls book, all of us girls cried, some of us openly, others with our heads down on our desks. I imagine for most of us the death of family pets wasn’t something entirely new, but we’d probably never read or heard it described so vividly. L’Engle’s book was a bit more complex with its mix of fantasy and government intrigue that has a young girl searching for a father who has disappeared. My tastes now run to the likes of Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende, Rudolfo Anaya, Lorraine López, Sherman Alexie, Leslie Marmon Silko, Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Barbara Kingsolver, and so many other fine writers. Still, the L’Engle book was memorable enough that several years ago, I was moved to buy a copy of this children’s book and re-read it.

MUZZLING TEACHERS?

MUZZLING TEACHERS?

I wonder: Would Mrs. Beckett be allowed to read such works to kids today or would she be prohibited from doing so because they might elicit emotional reactions from kids? Would she be accused of opening up children’s minds to things they’d never consider otherwise?

Early in my adolescence, my mother discovered other book mail order companies. What they were, I don’t recall, but because of them I read about every topic under the sun. Between the library, mail order books, and later on, high school classes, I read Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar; Go Ask Alice (by Anonymous or Beatrice Sparks, depending on who you believe); Daniel Keyes’ Flowers for Algernon; Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got his Gun; George Orwell’s 1984; and John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. Those are just a few of the titles I remember that made deep impressions on me. Johnny Got His Gun was particularly chilling in that I’d never before imagined a life in which a mind could be trapped forever in a limbless body.

So many other books crossed my path, books with titles I don’t remember but that also dealt with difficult subjects. Sometimes, books just appeared in our house, occasionally because my mother would go down a mail order list and select one or two for me, seemingly at random. Some had rather mature themes, and I’ve never understood if she selected these out of ignorance due to her newly acquired English, or because the book covers appealed to her in some way. Whatever the reason, it meant that I became familiar with bored, neglected wives who had affairs. Sometimes they kicked off their shoes and danced alone in their basements as I, a young girl in a Texas border town, watched. I learned that people drank martinis, highballs, screwdrivers, and other cocktails that were never in our home and that I wouldn’t taste for years to come. My mother couldn’t have known that I heard people swear colorfully in these books. She couldn’t have known that I was in the same room where hippies alternately smoked dope and meditated, that I stood on the sidewalks and watched them march the streets and hold peace rallies. I hope she didn’t know that I watched as the women took off their shirts and exposed braless chests for their boyfriends’ lips, or that I watched as others masturbated, made love, fought, shouted, gave birth, even raped and killed.

Perhaps I’m wrong, though. Maybe my mother did know all of these things and never told me. At any rate she never seemed to fear that I would turn out like the least savory characters in my books, or that I would decide to smoke pot, remove my shirt in public or kill somebody because of what I read. She didn’t seem to fear that books would lead any one of her children into seditious or treasonous behavior. Maybe she simply trusted that she had given us the appropriate tools to enter these new worlds and return home without having lost the sense of who she expected us to be. Maybe, she just felt it was important to allow us to discover the people, issues and injustices that exist in the world, knowing that one day, we would need all of this information in order to choose the principles by which we would live the rest of our lives.

THE LASTING LEGACY OF BOOKS

Once, I found a book on our shelves titled, simply, Genoveva de Brabante. Where it came from, no one seemed to know, but its spine had been ripped away exposing the binding. The covers were frayed at the corners and clinging to the book by a few threads. Curious, I opened it and in a couple of sittings read the Spanish tome in its entirely. Set in the 1200s, it’s about a woman wrongly accused of infidelity and shunned by her husband until he realizes his error. Though it is more fable than novel, I was charmed enough by the story to describe it to my mother. This one she knew well, remembering the times it was told to her and her sisters: “Hasta llorábamos cuando nos contaban ese cuento,” she said.

Aha. So my mother, too, had been moved by stories as a kid. Was that part of the reason why she seemed to care only that we read, and not much, if at all, about what we read? Did that, plus the fact that she wanted her American-born children to know a wider world than that the one into which she’d been born, also contribute to her and my father’s attitude about books?

I don’t suppose I’ll ever know the full answer to the question, since my father is now 80 and my mother’s dementia has erased the meaning of the word “book” from her mind. Plus, in her later years, my mother increasingly turned to her Catholic faith and made an about face on what she deemed to be appropriate reading material. She began questioning any book that had “occult” elements or themes and started collecting, instead, books about saints, Catholic figures, and prayer. Without a doubt, there are many volumes on my shelves that she would probably not like today. Sadly, even the books she most loved in the last decade are not safe from her disease. Over Christmas I visited her and woke up in the middle of one night to discover her tearing pages from one of her prayer books and shredding them with her fingers.

READ BANNED BOOKS

READ BANNED BOOKS

Still, her legacy lives on in my home, where every room contains books: On shelves, chairs, nightstands, coffee tables, and end tables; in drawers, in closets, on the floor, under beds, on a piano bench; on iPads, Kindles and computers. They are novels, historical non-fictions, biographies, memoirs, anthologies, and poetry chapbooks. At one point, in an effort to bring some order to the literary chaos in my house, I even boxed up my least favorite books and put them in the attic for safekeeping because, though less beloved than others, I couldn’t bear to part with them. I needed to know they would be there if ever I needed them. Even those ideas and stories in them that I didn’t much like had become such a part of my world that cutting them out of my life was like shuttering a part of my mind. It was akin to closing one of the many doors that had been opened to me.

Which is why I urge parents and students in Tucson to seek out the books removed from these classrooms. The freedom to read them in school may have been curtailed for now, but they are surely available elsewhere—in bookstores online or in your city, in the homes of adult friends or local writers. Find them, open their covers, and discover and explore the worlds that others would close to you so that you can make up your mind about what they mean to you. I’ll be reading them along with you.