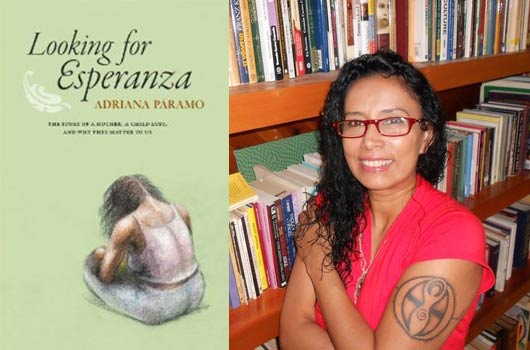

Colombian author and mother Adriana Páramo’s brother and father left her family when she was seven, so she grew up in a household of women: her mother, four sisters and aunts. Her powerful new book, Looking for Esperanza, is also about women: undocumented immigrants trying to make a better life for themselves and their children.

Páramo was born and raised in Colombia, but in 1992, she and her young daughter left Colombia for Alaska. Her daughter is grown now, serving in the Navy and about to get married.

Páramo says, “We don’t see eye to eye on many things, but we agree on what counts: Juan Luis Guerra’s music is out of this world, tamales make a great breakfast, there is nothing as delicious as jugo de guanábana and we both know by heart Tito Fernandez’s poem La Mañana.

Mamiverse: How did you become a writer?

Páramo: I truly think that it was decided on the day I was conceived. Imagine my father (a book lover) and my mother (a hopeless romantic). Mix these two ingredients with five older siblings (avid readers) and sprinkle my childhood with boleros, cha-cha-chas, magical realism and Neruda, and you get a writer. And if I had doubts as to what I should become when I grew up, Mom was always there to remind me who I was and will always be: un ratón de biblioteca.

Mamiverse: What were the most difficult obstacles you had to overcome as a Latina writer?

Páramo: I learned to speak English after I came to this country 20 years ago, when I was 26. I have a thick accent, which is by now part of who I am. When I got accepted into the graduate Creative Writing program at the University of South Florida, I was in my 40s and the only non-native speaker of English in the classroom, the only one who had never read Yates, Plath, Atwood, Faulkner, Toni Morrison, and many more. It was very humbling and outright terrifying to realize the huge amount of literary knowledge I lacked compared to everyone in the classroom (some of them young enough to be my children). I grew up reading Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Benedetti, Pablo Neruda, Eduardo Galeano, and Vargas Llosa, among others. Later in life, as an anthropologist, I spent a lot of time reading little known African, Asian and Middle Eastern authors whose nonfiction work—mostly ethnographies, fieldwork, and travelogues—filled my book shelves and imagination with fantastic stories of people across the globe.

Mamiverse: How did this project become a book?

Páramo: Looking for Esperanza, was not meant to be a book. I embarked on a journey to track down a Mexican woman who crossed the border to the USA, on foot with her four children, in a desperate attempt to create a better life. When her youngest daughter died of dehydration halfway through the desert journey, Esperanza strapped the body of her child to her own and continued on. Initially, I looked for her because she was a woman like me, a mother like me, an immigrant like me. I thought about my own mother who, before I was born, moved to Ecuador when she was pregnant with my fifth sibling. Imagine, a poor woman crossing borders with five children in tow; diving blindly into the unknown just because a foreign country offered better possibilities than her homeland. Esperanza also made me think of my own role as an immigrant mother. I migrated to the US with my five-year old daughter, like Esperanza, in a desperate attempt to create a better life. The main difference between the two of us is that we had a piece of paper saying that we were welcomed. Esperanza didn’t even have a passport.

Mamiverse: What was the most difficult part of this project/book?

Páramo: I went looking for Esperanza up and down the Florida Peninsula. In vegetable fields, citrus groves, ferneries and packaging houses, I found an underground culture of hungry undocumented women, and what did I have to offer in exchange for their stories? Nothing. Nada. All throughout my journey, I was plagued with feelings of inadequacy and helplessness. I felt useless. Other than buying a few groceries here and there, blankets, and toys; besides giving them rides and working alongside them, there was nothing I could do for them. Nothing. That was the most difficult part of the research and it was this realization which compelled me to turn their stories into a book-length manuscript chronicling their plight.

Mamiverse: What do you hope this book will do for the people who read it?

Páramo: Let me share with you the last paragraph of the book which answers your question: “It is my hope that these women’s words are read the way they were told to me: with their wrists and their hearts, with rage and fire and love. It is also my hope that maybe one day I’ll get the chance to see them again in a better place where they are no longer faceless wetbacks, but women, like me.”

I hope the reader trusts me enough to take this journey along the peninsula with me, that she loses herself in the triumphs and losses of these women only to emerge from it shining with humanity borrowed from their endless fortitude.

Read Related: The Temptation: Alisa Valdes on Her New Novel, Love & Paranormal Activity

Mamiverse: What are your goals now that this dream of publishing the book has become a reality?

Páramo: Right now I’m focused on promoting Looking for Esperanza. This is my first book-length publication and although I’ve been published in various literary periodicals across the nation, I know nothing about the business side of writing. Every step is a new learning process. My Mother’s Funeral, a memoir about being a woman in modern Colombia is scheduled to come out in print in 2013. In the meantime, I’m planning on revisiting and rewriting Desert Butterflies, a book about a group of women with whom I became involved while living in Kuwait. I also run a travel blog which gets weekly updates, and I’m working on a couple of pieces I was asked to contribute for a couple of anthologies. All in all, I’m in a very good place. No me espera ni dinero ni fama, but I feel immensely fortunate.

Mamiverse: Do you have any advice for Latina moms out there?

Páramo: Háblele a sus hijos en español. Many of the women I interviewed had children who didn’t speak Spanish or were rapidly losing their grasp of it. It’s such a shame to see a Latina mom (who doesn’t speak English) desperately trying to communicate with her own America-acculturated children in a patois of sorts, in a made-up language without roots and without history that’s neither English nor Spanish. I don’t read in Spanish as much as I’d like to, but that’s the only language I communicate in with my siblings, for which I’m very grateful. As a writer I benefit immensely from being bilingual. Spanish is highly flexible; it allows you to create some linguistic combinations that make sense only in Spanish. It’s also immensely lyrical, with more poetic possibilities than any other language I know of. And more to the point it’s a language in which you can use two or three negatives in a row, and be right: no me preguntes que no sé nada de nada.